Decrypting Catalan Numbers

In this blog, we will be discussing a very interesting number which often shows up in many kind of combinatorial problems, and the derivation of this number using something known as Reflection Principle, using which we will solve some cool probability puzzles, which may be seemingly difficult otherwise!

Let’s start with the main problem of this blog:

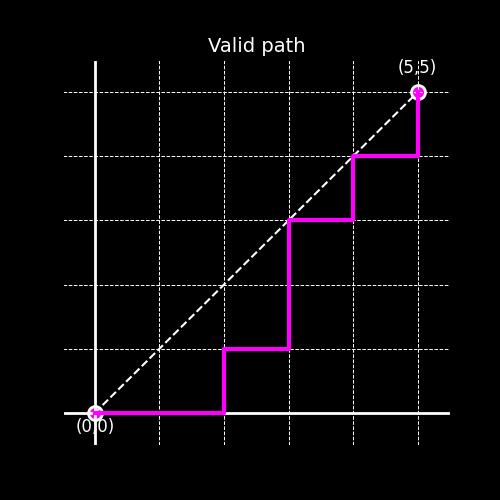

Imagine a 2D coordinate system, and you start at the point \( (0,0) \) and want to reach the destination at \((5,5)\). You are only allowed to take two type of moves, a unit right , i.e., \((x,y) \rightarrow (x+1,y) \) ,or a unit up, i.e., \((x,y) \rightarrow (x,y+1) \), but the catch is you can’t cross the line \(y = x\), in otherwords, always stay in the region \(y \le x\). How many such paths are possible?

Example of a Valid Path

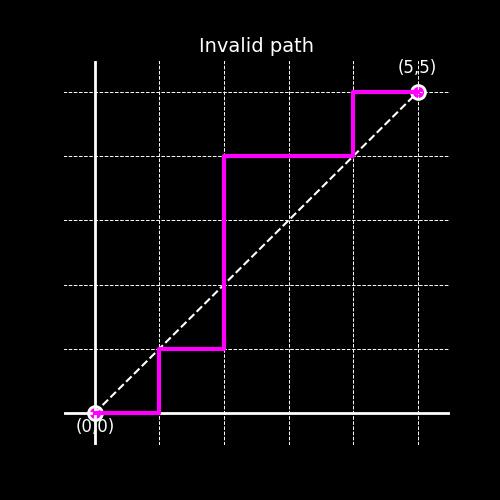

Example of an Invalid Path

As clear from the example above, the image on the right, violates the rule at the point \( (2,2)\), where it takes an up move, and crosses the line \(y=x\). If you would like to try this problem yourself, this would be a good place to stop.

As the title suggests, the answer is indeed given by the Catalan Number: \[ C_5 = \frac{1}{6} \binom{10}{5} \] Kudos, if you were able to solve this by yourself, if not don’t be disheartened, this is not a trivial problem, hang on for the elegant solution.

The Reflection Principle

Also known as the Method of Images, you might have come across this term in Electrostatics, it is quite similar to it, if not, I have got your back!

First of all the \( \binom{10}{5}\) might look familiar to you. It’s nothing but the number of paths from \( (0,0) \) to \( (5,5) \), using our described moves, just without the restriction of crossing the line.

See this if you are unsure about the \( \binom{10}{5}\) term Visualise it like this: you have \( 5 \rightarrow \) and \( 5 \uparrow\), you just have to keep them in any order, which will result in a path, and the number of ways to do so is exactly \( \frac{10!}{5! \cdot 5!}\), which is a direct result of permutations with repetitions

Now, from these paths, we will have to remove the number of invalid paths like the example shown before. Here we will use a nice reflection trick as described below:

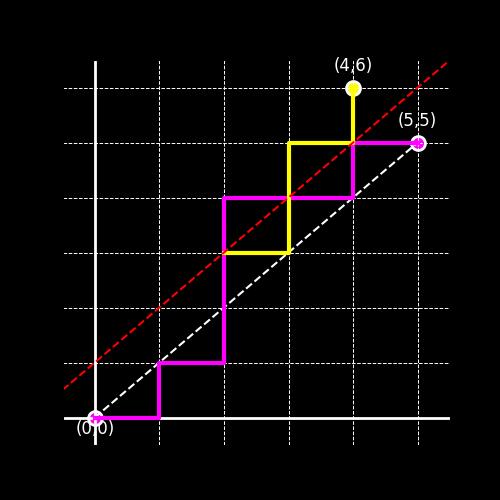

Consider the first time, an invalid path crosses the line \(y=x\), reflect all the moves after this move about the line \(y=x+1\), this means, all the right moves becomes up and vice versa. For the invalid path above, the given reflected path looks like:

Reflected path shown in yellow

The path first crosses the line at the point \((2,3)\), then after that we just took the reflection about the line \(y=x+1\) (the higher diagonal). Now, our destination seems to have changed to \((4,6)\), which is precisely the mirror image of the point \((5,5)\) about the line \(y=x+1\). Infact, if you draw all bad paths, and apply this reflection, all of these paths will end at \((4,6)\).

Proof of this claim Notice, the only way to “enter” the region \(y>x\) is when your latest move is an up move, and before that since we were at the line \(y=x\), it means we had equal number of up and right moves, so upto the violation point we have exactly one more up move (\(U\)) than right move (\(R\)), i.e., \(\text{#}U = \text{#}R+1\). As the total number of \(U\) and \(R\) moves are fixed (5 in our case), so let the number of \(R\) moves till the point of violation be \(x\), so number of \(U\) moves is \(x+1\). After this in our invalid path, we will have \(5-x\) and \(4-x\) number of \(R\) and \(U\) moves left resp., but we inverted them, so they become \(4-x\) and \(5-x\) resp. Hence, our final destination will be \((x+4-x,x+1+5-x)\), which is exactly the point \((4,6)\).

Now, I claim an even stronger statement:

Claim: Let \(S\) denote set of all invalid paths to \((5,5)\), and \(T\) denote set of all monotonous paths (only right and up moves) from \((0,0)\) to \((4,6)\) . Then we will have,\[ |S| = |T| \]

Proof: First of all we represent a path as a string of \(R\) and \(U\)’s, each of length \(10\). Next, we will define a bijective function \(f: S \to T\), following the reflection principle we just saw above, i.e.., invert the string (\(R \leftrightarrow U\)) immediately after the point when \(\text{#}U = \text{#}R+1\) in the prefix. Clearly, this function is well-defined as an invalid path is guaranteed to have such a violation point (as shown in the proof before). We now show the injectivity and surjectivity:

Injectivity is trivial, because if \(P_1 \ne P_2\), then clearly, \(f(P_1) \ne f(P_2)\) from our construction.

For surjectivity, consider any \(P \in T\), if we apply the same function \(f\) to \(P\), we will now a get a path \(P’ \in S\) with \(f(P’) = P\). Since, the destination is \((4,6)\), thus it must cross the line \(y=x\) at some point because of monotonous paths and hence, \(\text{#}U = \text{#}R+1\) at some point. Now, since reflection is about \(y = x+1\), the destination now becomes \((5,5)\). (proof is exactly the same as the previous one), and clearly this is an invalid path.

Thus, the claim follows from the bijectivity of the sets. \(\square\)

Now, calculating \(|S|\) has become a piece of cake, as \(|T| = \binom{10}{4}\) (again a direct result). Thus, our desired number of valid paths is nothing but the total number of paths less the number of invalid paths, or \[ \binom{10}{5} - \binom{10}{4} = \frac{1}{6} \binom{10}{5} \]

Getting us our desired result! Now you can see there is nothing special about the point \((5,5)\), thus we can generalise this result for valid paths till \((n,n)\), where \(n \in \mathbb{W}\) to get the general Catalan number: \[ C_n = \frac{1}{n+1} \binom{2n}{n} \]

Some more combinatorial problems

Having seen the Catalan number as a solution of a combinatorial problem, I would like to discuss some more problems, which may seem to be very difficult at the first glance, but becomes peanuts using Catalan number.

Problem 1 : Number of Dyck words of length \(2n\)

A Dyck word of length \(2n\) is a string consisting of \(n\) \(X\)’s and \(n\) \(Y\)’s such that no initial prefix of the string has more \(Y\)’s than \(X\)’s. (\(\text{#}Y \le \text{#}X\)). Counting these can be tricky if you don’t know the reflection trick, but if you notice, this problem is exactly the same as the grid problem with \(X = R\) and \(Y = U\). Thus, the answer to this counting problem is also \(C_n\).

A natural extension of this problem is to replace \(X\)’s with “(“ and \(Y\)’s with “)”, thus also giving us the number of correctly matched expressions containing \(n\) pairs of parantheses.

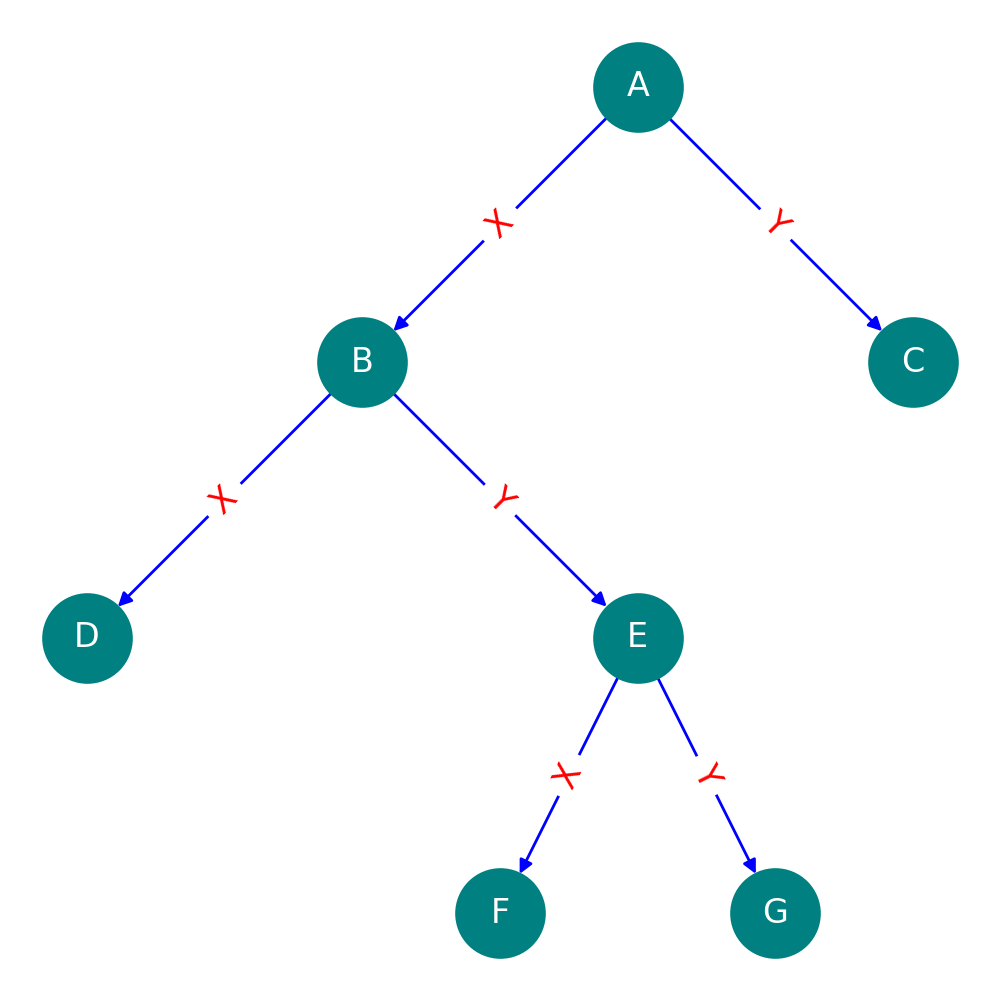

Problem 2 : Number of full binary trees with \(2n+1\) nodes

This is also a nice counting problem (and difficult too), which one may naturally try solving using recursion (go for it!). Let’s try solving this using problem 1. Label each left edge with \(X\) and right edge with \(Y\), and then do a dfs, going to the left edge first and then the right one each time, and then you will get a Dyck word of length \(2n\). Let’s see an example:

Labelled full binary tree with 7 nodes

If we compress this tree as described above, we get the string \(XXYXYY\). Clearly, it will always have \(\text{#}X = \text{#}Y = n\), by definition of a full binary tree. To see, it will never have \(\text{#}Y > \text{#}X\) in any prefix, we note that we always compress the tree to a string by traversing a left edge first, so if \(\text{#}Y > \text{#}X\) for some prefix, will imply that there is a missing left edge for some node, which contradicts the definition of a full binary tree.

Hence, once more, we get the solution of a seemingly unrelated problem as \(C_n\).

Problem 3: A probability problem related to ballots

As promised let’s look at a cool probability problem, which can be solved using the reflection principle:

Consider an election with 2 candidates: A receiving \(p\) votes, and B receiving \(q\) votes, where \(p > q\), now let’s say we count the ballots in an order listing them as we do (ex: “ABBBAA..”, note that each trial is independent of other), what is the probability that while counting, B is never ahead of A?

By now, this might seem doable, in fact it uses the exact same idea of reflection principle, label an A vote as \(X\) and B vote as \(Y\), but this time our destination is not \((n,n)\), but it is \((p,q)\), but the idea still works, hence the number of valid countings comes out to be: \[ \binom{p+q}{q} - \binom{p+q}{q-1} = \frac{p+1-q}{p+1} \binom{p+q}{q} \] Note that, in the above formula it is assumed that \(q > 0\), but if \(q=0\), the formula is still valid. (Only 1 possible sequence)

Since, the total number of possible countings can be \(\binom{p+q}{q}\), we get our desired probability to be \(\frac{p+1-q}{p+1}\). Now, one can easily use this result to solve the Bertrand’s ballot theorem, as \[ \frac{p}{p+q} \cdot \frac{(p-1)+1-q}{(p-1)+1} = \frac{p-q}{p+q} \]

Why? If in the very first count B is ahead of A, then it is not possible for A to be strictly ahead of B, hence first vote has to be for A, now after that, #votes for A can be \(\ge\) #votes for B, because the first vote for A will guarantee the strict inequality, and each trial is independent by definition, hence we multiply these probabilities.

Thus, the number of countings such that A is strictly ahead of B, is \(\frac{p-q}{p+q} \cdot \binom{p+q}{q}\) (probability times number of total sequences). Let’s put \(p = n+1\) and \(q=n\) (\(n \in \mathbb{W}\)). We get this to be equal to: \[ \frac{1}{2n+1} \cdot \binom{2n+1}{n} = \frac{1}{n+1} \cdot \binom{2n}{n} = C_n \]

This problem definition, looks very similar to the Dyck words formulation, infact it is! From the definition of the problem, the first vote needs to be of A (otherwise A is not strictly ahead of B), so now we are left with \(n\) A votes and \(n\) B votes, with the condition that \(\text{#}B \le \text{#}A\) for any prefix, which is exactly the definition of a Dyck word of length \(2n\). Hence, it is not a coincidence!

Quiz: 50 people have ₹100 notes and 20 people have ₹200 notes, and they are in line at a ticket counter which has no money and which charges ₹100 for admission. If a ₹200 note is presented and there is no change, the line stops. What is the probability that the line will stop?

Solution This is just the complement of problem 3, the answer will be \(1 - \frac{31}{51} \approx 0.39\)

Now, I have two challenge questions (mail me your solutions), correct solutions (proof required) will get my appreciation and special mention on my next blog:

Challenge 1: Find the number of \(n\)-tuples \((a_1,a_2,\dots,a_n)\), \(a_i \in \mathbb{Z}, a_i \ge 2\) such that in the sequence \(a_0a_1a_2 \dots a_na_{n+1}\),

\(a_i \mid (a_{i-1} + a_{i+1}) \, \forall i = 1,2,\dots,n\). Assume \(a_0=a_{n+1}=1\) and \(p \mid q\) means \(p\) divides \(q\).

Challenge 2: Find the number of \( n \)-tuples \( (a_1, \dots, a_n) \) of positive integers such that the tridiagonal matrix

\[\begin{bmatrix} a_1 & 1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 1 & a_2 & 1 & 0 & \cdots & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & a_3 & 1 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & a_{n-1} & 1 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots & 1 & a_n \end{bmatrix}\]is positive definite with determinant one.

Hope you enjoyed the blog :)